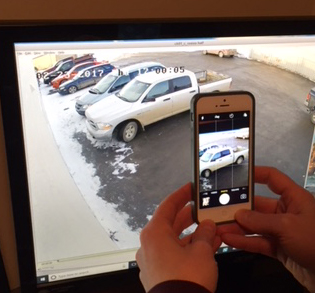

The proper method of presenting surveillance video evidence at trial is to show all relevant authenticated images that have been exported from the DVR or server. Occasionally, the only evidence of the original video that exists is photographs taken of the video monitor at the surveillance location. This less than ideal situation can arise for a number of reasons including the following:

- Not having the required hardware to export the video from the DVR or server.

- Not having the required knowledge to properly export the video from the DVR or server.

- Some systems are so old that they do not have an output function.

- Time constraints may mean than an officer will photograph the screen because the image is urgently required and there is no follow-up to properly gather all the video evidence before it is overwritten.

- Not being allowed to export the video.

To be clear, photographing the monitor is not the preferred method of capturing video evidence. While such photos will at least show what was on the monitor at the time the photo was taken, the original evidence is not available for a qualified forensic video analyst to examine and enhance. Considerable valuable evidence is often lost as a result. Conversely, photographing the monitor is preferable to having no images at all and seeking to rely on the evidence of a witness as to what was observed on the monitor, with the predictable inadmissibility ruling, exemplified in Commonwealth of Massachusetts v. Connolly, (2017) 91 Mass.App.Ct. 580 (Appeals Court of Massachusetts), which is discussed in an earlier post.

In United States v. Hicks, 27 Fed. Appx. 577; 2001 U.S. App. LEXIS 27085 (6th Cir. 2001), the defendants were charged with bank robbery. Part of the evidence against them consisted of stills that were obtained from the bank’s surveillance camera system. These stills were created by photographing the video monitor and by digitizing images contained on the original analog surveillance tape. The defendants argued that the stills were not the “best evidence” of the original images and that they had not been properly authenticated and may therefore contain altered images.

The Court of Appeal noted that under Federal Rule of Evidence 901, photographs are admissible provided the content is authenticated. Under Rule 1001(2) “photographs” include videotapes. The Court held that the stills were admissible as “duplicates” as they had been sufficiently authenticated. Accordingly, the challenge based on Rule 901 failed.

A Canadian example is found in R. v. JSC, 2013 ABCA 157 (Alberta Court of Appeal). The Court considered image authentication in circumstances wherein the trial judge admitted photographs taken of a video monitor and police testimonial evidence of what was seen on the monitor, even though the actual video itself was not entered into evidence. At trial, defense counsel unsuccessfully argued that admission of such evidence violated the best evidence rule, asserting that the video itself should have been entered into evidence.

As to the evidence of the officers who viewed the video, the Court stated:

16 In our view the best evidence rule does not preclude the admission of viva voce evidence of persons who observed the video (see R. v. Pham, 1999 BCCA 571 (B.C. C.A.) at paras 18-25, (1999), 139 C.C.C. (3d) 539 (B.C. C.A.)). However, the evidence may vary greatly in its weight and reliability. In this case, the trial judge was entitled to admit the evidence of the police officers who testified about what they observed in the video, and to give it the appropriate weight. It was only one item among several pieces of evidence which the trial judge found to be confirmatory of the identification evidence.

On the issue of admissibility of the photographs of the video images, the Court ruled that photographs are admissible if they accurately represent the facts, are not tendered with the intention to mislead and are verified under oath by a person capable of doing so. The officer’s evidence was sufficient in this regard.

Relying on photographs of a monitor is an unenviable position to be in for counsel. Proper authentication requires evidence of the system that captured the image initially, the number and location of cameras, and whether the images have been altered in any impermissible way. A photograph alone cannot answer those questions. Nor can it answer the important question of whether the photograph fairly and accurately depicts that event that occurred. The benefit of having all of the relevant video is that the viewer can see all images that were captured rather than being relegated to a photograph that may have been taken out of true context.